When tile were everything

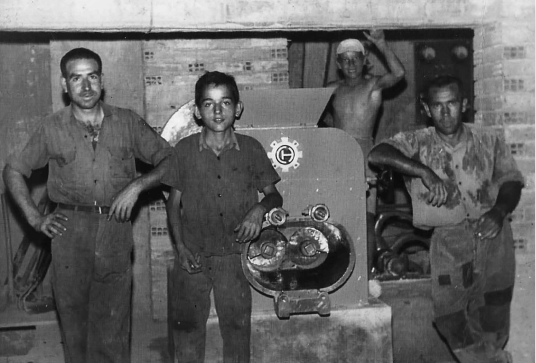

In homage to Domingo, Vicente, Francisca and Salvador Sempere Morera, and the son of his older brother, also Domingo Sempere.

I was born – without looking for it or asking for it – in the epicenter of a brick-making family. My mother, Maria la Gòria was the eldest daughter of Vicente Sempere Morera, the second of the four Sempere brothers, the Gòrios. It was my great-grandfather, Domingo Sempere Santapau, who established the first family “rajolar” (ceramic tile workshop) by a “sequer“ (drying area) near the Camino de las Minas, at the end of the Paseo de Els Rajolars. Initially he made terracotta roof tiles by hand with mud and then later floor tiles. Oliva’s ceramic tradition comes from many years ago. The Iberians already had a space near the Castellar where they buried their dead with large ceramic urns. And at least two Roman furnaces testify to the fact that amphorae were already being made in our village at that time as well.

Dust and mud transformed our land into economic business over the years representing the main source of local income along with agriculture. The tiles were made using the upper part of the leg as a measure, from the knee upwards, and then they were allowed to dry in the sun and cooked in the wood oven. The most important transformation of the company was carried out by the sons of the founder: Domingo – who died in the Civil War and was replaced by his son, also Domingo – my grandfather Vicent, my uncle Francisca, “the one of the sale”, who was the third, and lastly my uncle Salvador, the smallest of the four.

At home, when I was very young, I remember that we were always talking about “the factory”, that is, about our “rajolar” – about the things that happened, about the lives of the people who worked there and – above all – about the family events that happened around them. My grandfather, Vicent, left us on 7 February, 1974, at the age of 63, when I was still only a spring chicken. I remember him as a cheerful person who quite liked to drink wine from a vessel called a porrón or ‘catalana’, and sing with his brothers and nephews. He was always wore a loose-fitting shirt. When they all got together, it was a big party.

Memories of the daughter of one of the owners of the San Francisco de Asís factory, Vicente Sempere: Maria Sempere

“The factory was built by my grandfather, Domingo Sempere Santapau. I remember that when I was small I went to the “rajolar“ with my brother, since my grandparents were summering there. It was in front of the Veses estate, on the road to Els Rajolars, and next to it was Uncle Gascó’s property, where he had his vegetable garden. Often on Sundays we would go up there for our afternoon snack. The furnace where they cooked the tiles adjoined the road. My father Vicente Sempere Morera and my uncles Francisco and Salvador made the tiles by hand, with help from my cousin Domingo, who was the son of the older brother, Domingo too.

There were many fig trees surrounding our little factory, I remember one of them was right next to the road by the furnace and produced small but very sweet figs. There was a very large area where workers, crouching down, used wooden moulds to make the tiles with the mud from the land they brought from our mine, and they mixed it with the water from our large reservoir, which was surrounded by more fig trees. Although I also remember that we had other fruit trees. With the prepared earth and the water they made the mud, and the mix was put into esparto grass “cabassets“ which formed a rudimentary mould, as rubber did not exist yet. And they sold the wagons, which were used by the bakers who were going to make firewood in the mountains, to run the furnace that baked the tiles. I remember there was a mould to make the tiles and then they refined it. Back then they made adobe bricks and tiles by hand.

It would not be until many years later that they bought the first tile machines. I was older by that time and I remember they made a round furnace to cook them in. Back then the bakers took turns, some worked at night and some during the day. From that point on they began to make hollow bricks for partition walls. The office was established and we had first Jorge Maurí, Enrique Gregori and then Miguel Berbegall as administrators.

Over time they put in phones for everyone and we also bought our first cars from the money brought in by the tile factory: Seat 600s, and mine had the license plate Valencia 163161. I remember they also sold a part of the mine, but we also bought a large share at Elca.

At the end of the day they wanted to change the machinery, but it didn’t work out well. And then the moment had passed. Before they used to take the tiles to places like Benitachell, Cullera, Moraira and Teulada. The Sicania Hotel on Cullera beach was built with bricks from my factory that were never paid for, we never received payment. Other customers also ended up in debt for the bricks they ‘bought’. In the end this all resulted in us having to close the factory. To pay for the machinery we had to sell half of the Elca, but times had changed, our bricks were not so in demand because concrete blocks had come onto the market and it was no longer as profitable as before to work in ceramics.”

The perspective of a worker at the San Francisco de Asís factory: Diego Sanchez

“It was the year 1955 when we came to Oliva – us three brothers and my father. We came from the village in Jaen called Ruso. We came to find a better life in a place where there was work. We worked with Agalla, at the Rajolar de Sempere and then from 1962 my father, my brother Juan Pedro and I found work at the Rebollet.

From 1959, at the Sempere factory, also known as “the one of the sale” my brother Juan Sanchez and Salvador García drove the Pegaso trucks, and I worked the machines to make bricks, like everybody. In the end there were about fourteen of us workers. Making bricks was good work. People used to say it was hard labour, but I think that if you were a good worker it wasn’t so tough. The Sempere brothers’ were businessmen who paid well, and kept everything in an orderly fashion. I was very comfortable there.

The trucks brought good soil from a small town next to Llíria and we mixed it with the local soil from the mine. Sometimes we had to go and break up clods of earth with mallets into smaller clumps to improve the clay. We removed the stones. Then to the dryers, when it dried it was taken to the factory to make the mix.

At that time we were still very young. All the workers went together at seven-thirty in the morning, every day, walking along the Paseo de Els Rajolars to work. We’d go past Jesus’ store and buy anything we needed. Then we’d drop some people off at the Tercero factory, others at Benimeli’s, and others at Morera’s. We worked a schedule that started at eight in the morning until six in the afternoon. At one o’clock the siren sounded to stop for lunch and at two o’clock we had to get back on our feet.

I remember that at that time there was a lot of respect between the “masters” and the workers. I never got to work at taking things out of the oven, but there was a worker for that, also those who worked as “cremaors” or kiln burners. There was also a person who was responsible for cutting the tiles with a thread, when the mixture came out of the machine. We were tasked with using wooden carts to transport them.

My brother Juan, just like García, got along very well with the two carriers, and the Sempere brothers were very fond of them. They always kept the Pegasus trucks clean. If they ever made an unusual noise, it was immediately taken to the mechanics. Over time there were too many people and they always yelled at us. We knew that if the master wins, you win too. Us three brothers were always aware of that.

I honestly have a lot of good memories from that time. There was a lot of work, but also a lot of harmony among the workers. At mid-morning we would break for a bite to eat and sit around telling each other about our lives. We talked about girls and parties and going to the dance at the Apollo (Terrassa Mena), or to the cinema. We were fifteen or sixteen. We only talked about things like that, never about politics. However, the topic of football did come up once in a while. It was at the Terrassa Mena dance that I met my wife. On Thursdays we would play table football in front of the Apollo and the loser had to buy the drinks. With my friend Miguel Angel Vives, “the one from the go-karts”. We had a great time. Life back then was about working and enjoying leisure time with friends.”

A brief reflection by way of a conclusion

Oliva owes a debt to the ceramics sector, which formed the basis of its development throughout the twentieth century. A few years ago, the city council decided to illuminate the Els Rajolars chimneys, in acknowledgement of their importance. All of them are currently protected, but a more comprehensive plan is needed incorporating all of the Paseo de Els Rajolars, and – why not – the creation of a museum to teach about what this industry meant for the city. For example, an Interpretation Center that explains to future generations about the golden age of brick and tile making, when Oliva was the main city in Spain for tile production and elaboration, comprising thirty factories working at full capacity, almost all of them located in the Els Sequers area, although some were also located along the Pego and Dénia roads to the south of the urban centre.

Why not acquire the tile factory that is in best condition, according to municipal reports, and make it into a leading centre for research and the dissemination of knowledge about the world of bricks and tiles? To serve as a basis for future economic projects that may be related to the subject. Oliva, in this way, would repay its debt and feel proud of its past and, above all, of the future of this important urban space, converted to once more function as an economic engine of the municipality.